My generation grew up with the standard propagandist notion “as long as there won’t be war”. This would be used to justify future wars. Sometimes, these wars weren’t as direct and large-scale, as they didn’t take the form of combat such as World War I or II. In such cases, the majority of the population did not hear the explosions of bombs and munition, didn’t know what the frontline was like, nor the trenches, mud, cold and shelling. A lot of other crucial associations of war were also unknown. Those who lived in the Soviet Union after the Second World War tried to explain their hardships through the notion that they were the ones who suffered most from the war. If not for the war then… and the fantasy would carry one’s imagination into a new realm, without taking into account the fact that their country, even after 1945, continued to wage many wars, and the living standards never really improved. For example, the electrification of villages was only completed in the early 1960’s. Water supply, a sewage system and gas was not even in question. This was the same time that Germany, defeated and split into occupation zones by the Allies, had superior living standards. Outside of the government’s observation, the majority talked about small things and what they saw in Europe. However, everyone abided by the same mantra “as long as there won’t be war” and came to a consensus that the war changed their world.

A Transit Territory of Permanent War

The first novelists of the romanticist distinction at the end of the XVIII century, while examining the French revolution, discussed whether changes in the world should occur in a revolutionary or evolutionary fashion. Inspired by nature and the events in France, they were divided into two categories: the Volcanists and the Neptunists. The former considered that everything arises from catastrophes similar to the eruption of volcanoes, earthquakes, while the latter claimed that water and precipitation are the main powers present, as the slow geological process forms mountains, minerals and soil. The main question that endlessly bothers humanity: whether we want forty years in the desert or swift changes without knowing the consequences. Slow changes and reforms through the methods of making smaller steps or beheadings by guillotine. The gradual increase in welfare similar to the ripening of plants and the transition of children into adults in both humans and animals, versus the possibility of an instant result, a consequence of victory and looting during war. Those damned dilemmas. War in such circumstances always looked like an easy decision.

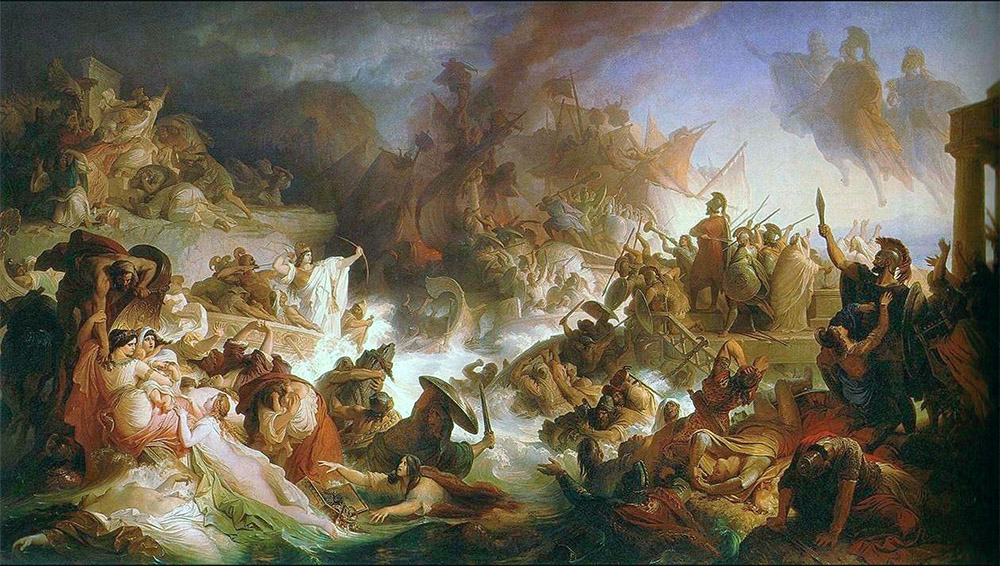

During the battle of Salamis, a crucial episode from the Greek-Persian wars, in 480 B.C. Painting by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, 1868

War was always inherent to humanity. All of our knowledge from the period of written history is connected to war. The course of any national history is impossible without war. Wars are perhaps the one major ways to imagine the ancient and the glorious past. The first written records about the territory of our country can be read in the ‘Melpomene” by Herodotus, in which he writes about the Scytho-Persian war. Melpone was considered the muse of tragedy and song, which amplifies her connection to war. However, Herodotus’s choice here could have been accidental considering his long history of work on the history of Greek-Persian wars and the description of the lands that they were happening on. Each one of such lands has a name. Strangely enough, millenia later, the places that were first described by ancient Greek historians in ancient Greek, are now the steppes of the Northern Black Sea Coast, where Ukrainian soldiers shoot down Iranian drones.

The Roman Empire, at the peak of its might, controlled part of this territory which was part of the Moesia province. Later, it was divided in half and the territory from the delta of the Danube to the Dnipro was part of Lower Moesia. Several wars occurred here as well. In the coming centuries, the steppes of Ukraine became a corridor in their own sense, through which the Scythians, Sarmatians, Huns, Avars, Bulgars, Ugrians and Pechenegs all passed through. Another empire, with its capital in Constantinople, which ruled over Black-sea coastal territories, dealt with them. Most of the time, it had to deal with them in the form of conflict, decided by power and thus being considered an indisputable empire, until the next time it came in contact with something unknown – similarly to the events of today.

Conquest and Peaceful Subjugation

Throughout our history, which concerns the central Dnipro lands and where Kyiv already plays the role of the main city, wars have become the main foundation of understanding political events of a new order that arose in the second half of the IX century under the name of Rus’. It was the wars that created the image of Rus’ that we see today in textbooks, the image of the biggest nation in medieval Europe. Did this image really correspond with the realities of that time? No. We are so fascinated with the descriptions left behind about Kyivan princes’ campaigns in the Danube, Volga and Caspian Sea regions, that we no longer take a minute to stop and evaluate this period of history to make sense out of it. What happened beside these campaigns? What do we know about life there during peacetime? War accelerates the pace of history. War gets all the attention to itself.

In stories that we know from various chronicles, wars are traditionally viewed as conflicts between two or more belligerents. This was so from the struggle for control over Kyiv between the first Scandinavian chiefs and their attempts to rob Constantinople. The breathtaking description from the Primary Chronicle by Nestor the Chronicler has a lot in common with reality, however, there were reasons to express ‘pride’ and glorify Knyazi and at the time. Afterwards, the sons of the Knyaz of Kyiv Volodymyr continued the legacy (the one who brought christianity to these lands). His sons, like the majority of Volodymyr’s descendants, competed for his royal inheritance. This continued through the next generations of this dynasty – their grandsons, great-grandsons and so on. Wars for power, where the main prize was the throne in Kyiv, allowing one to be the Knyaz to rule over all. This was a very distinct attribute that was constant over a long period of time, also confirmed by some of the oldest chronicles available. Similarly, Ukraine, is at war for a third of its time as an independent country (since 1991). This is quite a long time, a heavy weight to carry for one generation.

Knyaz Oleh in front of the gates of Constantinople. A Page from the Tales of from the 15th century Radziwiłł Chronicle.

In these old chronicles, Kyiv offloaded its power to a few other centers which then later resulted in the unification of a relatively large territory. This made the throne in Kyiv less tempting to take over, but rather the perseverance of one’s own centers such as in Chernihiv, Vladimir and Halych. Even though the creation of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia is viewed by our historiographic and subsequently our historical tradition as a crucial turning point, essentially, it came to be as a result of the war waged by the Volhynian Knyaz Roman Mstislavich against the Kingdom of Galicia. Without understanding this, it is difficult to imagine how such an event would ever pan out in a peaceful manner.

The Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia was supposed to become the biggest nation state created by the descendants of Rurik. Instead, wars and power struggles raged for inheriting the rights to the throne from Roman, the invasion of the Mongols and the subsequent battle losses proved one thing: the safety of one’s own kingdom and the indisputability of one’s authority and territory are all impossible without war. In fact, this is why the steppe-based empire of the descendants of Chengis Khan, which in the XIV century became the Golden Horde, held everyone around them according to their own arrangements. This would have continued further on, however, the agricultural population decided to expand and head east. This was done by a small kingdom which called itself the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. As it is happening again today, the military aid provided by Lithuania to Ukraine today is one of the biggest, if one counts it as aid per capita and size of the economy.

Moreover, during the second half of the XIV century and the first half of the XV century, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was successful in subjugating a large swathe of territory, becoming the biggest nation in Europe at the time – almost an empire. Throughout our history, the mystified events of the victory at the Battle of Blue Waters, gave birth to a peculiar myth about the soft power of the Gediminids. History is written by the victors. And even if Lithuanian chronicles that were written in the XVI century also described defeats such as the Battle of the Vorskla River, for the most part, the chronicles had stories of ‘peaceful’ subjugation of large territories in south-eastern Europe at the time.

Other contenders for the inheritance of the Rurik dynasty were not so lucky in terms of accepting those who were the creators of the modern Ukrainian historical sciences. Their military campaigns differed in their estimation and in their subsequent understanding of our history – pillaging, occupation, the Catholicization and the termination of property rights of the local feudal nobility. The Polish kingdom, which from the mid XIV century captured the southern parts of the Rus’, finally cemented itself on its new territories thanks to a royal intermarriage and its military alliance with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Furthermore, there was the Golden Horde, which as a result of the pandemic and power struggle among many competitors, fell apart into smaller entities. One of the parts of the former Golden Horde later became the Crimean Khanate in the mid-XV century. The reception of the Crimean Khanate in our history is only negative and was only seen through the prism of war and invasionary campaigns where the main aim was to gain a new supply of slave labor from their enemies.

War in the late medieval period and the early modern era was one of the core components of ‘honesty’ of any ruler. It is due to victory that a king or an important Knyaz would be able to hold their place and be remembered as a glorious and memorable figure in the chronicles that would reach our time. Everyone admires victors. Wars that occurred in the second half of the XIV century, have been shown selectively throughout Ukraine’s history. Perhaps, they are even best described not as wars but as sparks or moments when certain battles happened to be victorious. One such event was the battle of Grunwald in 1410 and the battle of Orsha in 1514. If representatives and banners from all of the relevant constituencies of modern-day Ukraine were present at the battle of Grunwald, then things were different for the battle of Orsha. The man who deserves the praise for success in the battle was a well known knyaz Wasyl Ostrogski. He won the battle, but eventually, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania lost the war with the Grand Duchy of Muscovy. In other wars, where historians observe a so-called ‘Ukrainian’ influence, they were never truly considered as their own in Ukraine. Instead, their own wars were here in Ukraine, on the terrain of the central-Dnipro and Podilia regions, where the two main contestants were the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire.

The Battlex of Grunwald. Painting by Jan Matejko, 1878.

These two nations, from the mid-XV century became our two biggest military opponents throughout our history. And if the wars between the Polish kingdom and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were not so frequent, perhaps even very rare, then the multiple Tatar invasions became a frequent sight and persisted with varying degrees of intensity until the termination of the Khanate as a state. In response to this of course, numerous armed resistances (both private and state-led) took place.

Cossack wars and Imperial Plans

The vast eastern frontier that passed through the territory of modern Ukraine was always in motion and hence thousands of soldiers tried to master the art of war. As a result, here in the eastern frontiers, came about the birth of the Cossacks in the second half of the XVI century. This process becomes dominant in the main historical narrative from here on in. This narrative is a militant one. The irony of history lies within the fact that today’s Crimean Tatars, citizens of Ukraine, fight for Ukraine’s territorial integrity, while Turkey’s indirect policies allow Ukraine to obtain modern weapons and other means of fighting this war.

The introduction of the Cossacks into the military campaigns by the Kingdom of Poland eventually led to the formal recognition of some of the Cossack formations. They were introduced to the royal register, received salaries, official banners, stamps, kettledrums – all of these things led to the creation of a separate identity and uniqueness. The other Cossacks that were not institutionalized and stayed at the Sich, represented a more diverse phenomenon – their main purpose was to find prey. Both groups, even though being quite cold and vary towards one another, could form combined forces of up to 40,000 men, such as they did in the war with the Ottoman Empire in 1621. This was a larger army than the Kingdom of Poland had during peacetime. This militarization continued to build up throughout the XVI and early XVII century in the Dnipro region – and subsequently exploded in 1648.

Mykola Samokysh’s “The fight between Maksym Kryvonos and Yarema Vyshnevetskyi”

From this period onwards, the war became part of everyday life for multiple generations covering a large territory that, perhaps, constituted the majority of the territory of modern Ukraine. It was the wars themselves, military campaigns and battles that became the historical image of our past. Wars tend to put forward those who lead their men into battle, those who are victories, those who suffer painful defeats and those who follow their leader in their hundreds of thousands – such as Bohdan Khmlenytsky, Ivan Vyhovskyi and Petro Doroshenko. The aim of the Cossack Hetmans at first was the recognition of their rights and privileges. With time, these aims developed into more – such as the need to become something separate. This was key to what later formed our understanding of our past. Without wars, the understanding of the past would be fundamentally different. In the early XVIII century, it all came to a boiling point – a historical intersection, which, despite several attempts, wasn’t resolved, even by such talented and experienced politicians as Ivan Mazepa.

The war, which started in the far north and where Muscovy’s Tsar Peter fought the Swedish King Karl the XVII, eventually spilled over to Ukrainian terrain. The union between Mazepa and Karl led to one of the most famous battles on Ukrainian territory, the Battle of Poltava in 1709, where the Ukrainian Hetman and his ally, the Swedish king, lost. This defeat gave way to the creation of a very unusual document known as the ‘Constitution of Pylyp Orlyk’. In this document, the Cossack notion of statehood took its shape. The document merely stayed a project, an idea for a small group of political emigrants that hoped to return to their homeland in victory one day and restore the former glory of the Zaoporizhzhian Cossack army. In the meantime, the Cossacks that remained on the left bank of the Dnipro, gradually started losing their rights and autonomy. By the end of the XVIII century, they became the subjects and serfs of the Russian Empire – all as a result of several wars that they participated in, in which the termination of the Crimean Khanate as a state took place and the Ottoman Empire left the northern coast of the Black sea. It seemed that wars lost their place in the world, as the main adversaries, as they were formed in the majority of historical literature, simply ceased to exist as political players. Meanwhile, the Empire had its own plans.

“Rejtan, or the Fall of Poland”. A painting by Jan Matejko, dedicated to the events in the Sejm in 1773, when Polish nobleman Tadeusz Rejtan tried to prevent the break-up of the Kingdom of Poland.

The Russian and the Austrian Empires, upon splitting the territorial gains following the dissolution of Poland in the late XVIII, gained a large fraction of territories of modern Ukraine. The Russian Empire, throughout the XIX century, continued to wage wars with a smaller intensity than before, trying to capture Constantinople in vain. One of these wars, known as the Crimean War, became the first war of its kind as it was the first time the steam engine was used (in ships), electricity was used for instant communication and correspondents were able to report back to the world without interruption. This war, which the Russian Empire lost, became the initiator of reforms that led to significant modernization. In the Austrian Empire, the war was the uprising of Hungarians against the Habsburg Empire, also led to a wave of reforms (slightly earlier than those caused by the Crimean War), which later drove the formation of modern nations in central Europe. The world entered the era of steam, electricity and fast change. Back then, like today, the victors were those who had the technological advantage.

A Modern Division of the World

The First World War, which had multiple participants to varying degrees, destroyed empires and changed the world order that was established after the Napoleonic Wars and led to the creation of multiple new nations. The price of this change was enormous – millions of lives. In this bloody mess, Ukraine arose from the ashes, and through war, the first modern Ukrainian state was born. Previously, a not so big group of national intellectuals and figures believed in Ukrainian statehood, while Ukrainians fought against one another in different Imperial armies. Revolutions were then supposed to bring an end to this. Upon the creation of Ukraine’s statehood after such a devastating war, it was supposed to materialize the dreams of many national thinkers and believers in a united Ukraine from the San river to the Don. Unfortunately, these dreams were too picturesque, and the vast majority of the politicians at the time, were not prepared to go all the way for the Ukrainian nation and break ties with the Empire. The Empire which, at the time, was preparing to take back what it lost.

The idea, which inspired the struggle, turned out to be difficult to execute. None of the Empires and other national liberation movements wanted to share a spot on the political map of new Europe. It was also difficult to convince the victors of the First World War of their own significance. MOdern wars are rarely victorious without allies and their aid. The Bolsheviks, from late 1917 have initiated their big vision of an Empire and did not see Ukraine as a partner or ally. They were talented at intriguing and manipulating the internal and external public with political slogans. In the meantime, Polish politicians had their own vision about their eastern neighbor and after waging war over Lviv together with the Ukrainians against the Bolsheviks in 1920-1921, they formed a new border that didn’t divide, but was rather unifying. The Ukrainian officials that wanted to save the Ukrainian People’s Republic, had no chances of doing so under such circumstances. Hence, they were on their own.

The declaration of the Third Universal of the Ukrainian Central Council at the Sophia Square in Kyiv in 1917.

After a series of short wars with Russian Bolsheviks, there was only one result – the agreement of Moscow to allow the existence of a Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic. Formally independent and governed by Ukrainian Bolsheviks, yet loyal and friendly to their colleagues in Moscow. After this, in late 1922, the two then created a union of Soviet Socialist Republics, that after 12 years, thanks to wars with Poland and Romania and in agreement with Germany, brought about the borders of Soviet Ukraine.

The Second World War, that started in 1939 formed Ukraine (without Crimea at the time, which was later adjoined to the rest of the country) ended up making Ukraine in its current borders, as recognized by the world today. Stalinist expansion and war led to most ethnic Ukrainian lands ending up within a single country. The price of this was extremely high. Millions of Ukrainians died in the war, consequences of which were felt for decades to come. Even if the war gave Soviet Ukraine a seat in the UN, that also partially facilitated Ukraine’s independence in 1991, it did not give answers to questions that were in the minds of Ukrainian prominent liberation figures in the 1920’s and 1930’s – independence. The hopes that the attempts of 1918-1920 would be successful in the Second World War were left in vain. Another 46 years were needed for the Soviet Union, which was already bleeding from multiple conflicts, to cease to exist. Empires may seem almighty at first, but they have the tendency to collapse all of a sudden.

Soviet Soldiers prepare to cross the Dnipro, 1943

Gaining independence in 1991 seemed like a miracle because no shots were fired in Kyiv on August 24th 1991, nor was there combat on the 1st of December, when the choice was made through an independence referendum and not a military campaign. It seemed that history took a peaceful turn here, unlike those of Lithuania, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Moldova. Peaceful independence was a miracle. It just didn’t fit into historical practices. The dissolution of Yugoslavia which was underway in parallel, was a staunch example of military action. Even if in 1993, when the Czechs and Slovaks went their separate ways peacefully, we still tried to convince ourselves with the illusions that there would be no more wars to come. After all, there were enough wars. The 20th century war count in Ukraine was so high that there was just simply no talk of it happening again in an independent Ukraine.

Today, from the perspective of three decades of Ukraine’s existence as an independent country, we are able to observe our own mistakes. Almost immediately after the 24th of August of 1991, Russia had already threatened Ukraine’s territorial integrity by fueling separatism in Crimea, through the constant delays in the decisions on their Crimean fleet, by depriving Ukraine from its rightful fraction of inheritance, creating unnecessary hurdles and simply installing their agents in Ukrainian institutions. This was already a war without shots being fired, but not less dangerous. We were in the midst of losing that war, as well as the war on the cultural front.

The culmination happened a few times. Before 2014, when Crimea and parts of Donbas were occupied, there was the incident of Tuzla in 2003, meddling in the presidential elections in 2004, the war in Georgia in 2008, the Kharkiv Pact in 2010 and the winter of 2013-14. This all happened despite no shots being fired before 2014 and no war was declared. The latter did not happen even until now. However, the scent of war was hanging in the air.

Leonid Kuchma during Russia’s attempt to occupy the Tuzla peninsula in 2003.

The war that broke out from the occupation of Crimea and Moscow’s usual attempt to create puppet states became a significant catalyst for Ukraine’s national rebirth. Without these events, we would still be debating about the direction our country should be heading, about who is and who isn’t a national hero and finally, the language of our country. However, the price of this realization, as always, is too high… as usual.

Overall, humanity is not very capable of managing change without wars. Every famous war throughout history, regardless of its name or reasons, always changed the world and its people, even if they didn’t notice it. Of course, calls for a just war (bellum iustum) remain the foundation of any propaganda. There will always be a certain amount of people that will try to justify war. “Carthage must be destroyed” (Carthago delenda est), – as Cato the Elder proclaimed. “Jerusalem must be ours”, – was the main war slogan of the First Crusade from the late XI century and is still used until this day, regardless of who proclaims it. Those who proclaim it may change, but the key point of the slogan stays the same. This can drag on for more than a thousand years. “To Berlin” was the main slogan of Stalin in 1944-1945. A few million died in order to fulfill the aim of this one person. Similar examples were abundant and may remain abundant in the future. If one pushes such slogans into the mind of the RUssian president, then his worldview will quickly change to “Kyiv must be destroyed”, where Kyiv wasn’t even seen as a city but as a means to govern, where power is high in concentration. “Kyiv must be ours” and “To Kyiv” are then merely existential and directional aims, which are of course, unachievable without war.

From our Ukrainian perspective, this is a challenge to Ukraine and its people’s very existence. And the modern war that broke out not on the 24th of February 2022, but in February of 2014, is fundamental to the creation of the modern Ukrainian nation and state. We have been trapped in a historical cycle for far too long, following the footsteps and repeating the mistakes of our predecessors in making harmful compromises with Russia. It has become apparent that this war in fact, has created the modern Ukrainian nation.