Nothing, except for a few sandbags that were left to cover the windows of the ground floor, really reveals the events of March 2022 in Chernihiv’s regional children’s hospital these days. Moreover, no one really wants to recall the events of March 2022. Time has distorted the terrifying events as well as healed some of the wounds that were inflicted. However, it would be impossible to completely forget the events.

On the 28th of February, shell fragments damaged leg of 11-year-old Vadym in his own yard in Kyinka, on the outskirts of Chernihiv. He was one of the first of those who were wounded in the war and who were taken to the regional hospital. His mother, Olena, carried him for a big part of the way to the hospital, as ambulances refused to go due to the constant shelling. If not for their neighbor who picked them up mid-way, she would have probably carried him till she would no longer have the strength to do so.

When the shelling began, Olena and two of her children were in the house. Their guest, a close family friend, Serhiy, was out in the yard. The Orcs were positioned nearby and thus were shelling the village directly. ‘At first, it was ‘Smerch’ (rocket system) that landed near the house’ – says Olena. ‘The house shook and I stood up. All the windows shattered, the door bent and opened. We left for the outside, but did not risk running to our neighbors who had a cellar. The shelling was coming from that direction. We knew that in that case we wouldn’t escape’. They then put the children on the ground and covered them with their bodies. ‘I lied down on top of our youngest one, Serhiy – onto our oldest son. Serhiy could not feel his body. Blood started flowing from his head and his 8-year-old son Ihor, whom Serhiy was covering from shell fire, started screaming. Meanwhile, Vadym started shouting about pain in his leg. “I looked closely…you could see everything, his leg was fragmented. He told me: don’t worry, I’ll get through this, Mr. Serhiy is doing worse, help him”.

Sadly, it was too late for Serhiy. He was still conscious for a moment, then started to grab the ground and shortly died. Olena bandaged Vadym’s leg up and shouted for help but no one came for a while. At last, their neighbors showed up, helped collect the children and covered the dead body of Serhiy. By the time Vadym was being operated on, Olena noticed that her own leg was in pain too. A fragment of a shell pierced through the flesh of Vadym’s leg while another one was still stuck: ‘When the surgeons were stitching up Vadym, the nurses fixed my leg up and bandaged it so that the kids won’t see it’. Olena spent two weeks in the hospital with her children, until the hospital was shelled. Being on the receiving end of artillery fire was not a joyful experience to say the least. Leaving a besieged Chernihiv was also not an easy task. Friends that arrived all the way from Kropyvnytskyi, evacuated their family through mined fields, as the main bridge over the Desna river was blown up the night before.

Moving to the first floor and the basement

Chernihiv doesn’t have its own city children’s hospital, so little patients from the city and the region are treated in the regional children’s hospital. 500 beds of this institution were rarely empty but after the 24th of February, everything changed. Children who were on a scheduled treatment were immediately released. The hospital does not have its own bomb shelter, so on the first day of the war, the basement was re-arranged in order to fit the personnel and patients. Every department had its own rooms in the basement meant for storage of things such as old beds, crutches and old boxes. All of this was thrown out or put into use elsewhere.

The air in the basement was quite damp. The walls were covered with fungus and there was no ventilation. As it turned out, such conditions were not a big problem for future patients. A lot of them would lose their homes and would be happy to pass the cold and bombardment in this manner. By the 25th of February, there were around 200 medical personnel and families, children who were on scheduled treatment who were not evacuated in time with their parents and local inhabitants from nearby homes. The hospital kitchen only had two or three women which prepared food for these 200. While Chernihiv was under siege, their hot soup was one of the locally preferred dishes. ‘During the battles, we worked as a hospital both for children and adults’ – said Natalia, a nurse. ‘If there is an explosion nearby, then the people who suffered from it are brought to us. We lived here with families. I only went home on Saturdays and Sundays in order not to burn out, it was difficult both emotionally and physically. If there was a spot to sleep in the ward in the basement… if there wasn’t, doctors would distribute mattresses in the corridors and people would sleep there in bags. There were dogs there… a rat, a rabbit and a cat’.

The photos are provided by the characters of the material

Due to the constant bombings, all the medical equipment from the surgical department on the sixth floor was brought down. In some of the small rooms, the windows were covered with sandbags. Surgery was done with headlamps in the cold. Afterwards, the patients would be brought down into the basement. Right in the corridor, cardi-pulmonary resuscitation would be done. Plaits would be installed. ‘Here, the wounded would be placed’ – says a children’s orthopedist and traumatologist Mykola Liutkevych. ‘If the wounds weren’t deep, we would block the blood flow and carry out life-saving surgeries under more moderate anesthesia. If it was something more serious and we needed deep anesthesia, we would take them into a different ward with a generator and all the necessary equipment’.

There were two generators. A large one, which was used to support the function of resuscitating, and another small one (3 kW) for everything else. ‘There were times when we started it up, started the surgery, started the respiratory equipment and we still needed to turn on the electric knife. We turn it on and everything goes black as there is not enough power. In such cases, the anesthesiologists would breathe through manual ventilators (instead of the child) – also known as Ambu bag valve masks.

Микола Люткевич

The doctors were sure that this was some sort of provocation that would soon come to an end. They never imagined that they would have to see this hospital filled with bodies of children and adults suffering from shell wounds or a man with an assault rifle from the local territorial defense who came to check on his kids in the hospital. The first wave of mass hospitalization due to the war happened on the 3rd of March. The Orcs dropped six bombs on a cardiac dispensary nearby. A few bombs hit a queue with a lot of children. As a direct result of the incident, there were 37 wounded patients. ‘It was the moment when, sadly, we had to categorize the patients… with the understanding that those who were heavily wounded couldn’t be saved. They were only given a small amount of aid as there was not enough for everyone, so they would focus on saving 10 children in the meantime. When a child is part of a car accident and an entire team of medical workers are operating the child, it is totally different to when there are 37 patients at once. It was chaos and disarray. I had to change my uniform twice because it was covered in blood. Soldiers, elders, children… ripped to shreds’ – said Liutkevych.

A few medical teams could operate a single patient

The hospital at the time had around 40 personnel out of the original 500, so it was necessary to keep working non-stop. Sometimes, even the parents of the children would have to work. The nurses were sometimes physically incapable of moving the heavy bodies of the wounded patients. ‘We made bandages for them and told them that we need a hand. They would go pale, red, lose their breath because they never saw so many wounds, so much blood and bones exposed, but nevertheless we did our best’. Still, even so, the medics were not prepared for such events. They were simply not prepared for the sizes of wounds. For example, as soon as they treated a wounded soldier (who’s wound was 30-40cm big), they realized that they had used up all of their bandages. ‘After cluster bombings – the entire body is covered with metal fragments. Around 30-40 fragments, and then we needed a lot of bandages of course’ – explains the doctor’.

‘People that were taken to the hospital carried with them a smell reminiscent of something burnt’ – said Natalia. ‘It was necessary to wash them in order to figure out where the wounds were. This was very emotionally difficult. I tried to prepare myself psychologically for what was about to come. The most important thing was to provide aid. It is also necessary to listen to the doctor and everything he says. If he orders you to start bandaging, even if it is scary, my hands do the job’.

Підвальна палата

Doctors tell us about how almost all of the wounded had various organs damaged. Hence, a lot of the time, different medical teams operated on the same children simultaneously. Ophthalmologists would stitch up an eye, traumatologists treated bone issues all while being aided by thoracic and regular surgeons. There were children who were operated on five times. Many patients needed a lot more complex surgeries such as reconstructive surgery which requires a lot of special equipment. However, due to the siege, this was impossible. Depending on the circumstances, such patients were evacuated to Kyiv or Lviv and then to the EU. The military and various volunteers helped a great deal in this regard.

“Together with my father, we went to the other side of town to our friends in order to charge our phones, when the cluster rocket bombing started’ –– says Bohdan. ‘I remember an impact, a bright light, and when I regained my focus afterwards I saw another explosion in front of me’.

The boy tried to get up but couldn’t as his leg was broken. When the shelling stopped, bystanders called an ambulance. His father was placed on a truck and taken to the regional hospital for adults. Bohdan was taken to the children’s regional hospital for immediate surgery. There were wounds on the right foot, left knee, a shell fragment in the eye and many shell fragments everywhere. After surgery, Bohdan was taken to the basement. Next to him, there was a boy with a concussion, a girl with a broken pelvis and another boy with a broken knee. ‘I was only scared of one thing – not being able to walk again’ , says Bohdan. Right before his release from the hospital, he found out that he would never see his father again. Many weeks passed between the shelling and this moment. According to Bohdan, his father died from a stroke three hours after the cluster shelling, ‘because he was very worried about me’.

‘During peacetime, we never thought that one day we would have a person that would collect arms upon entry’ – continues Mykola Liutkevych. ‘If one said so a year ago, people would call it fantasy. We were at a children’s hospital where the personnel walked around with silly hats, dolls, toy cars and other gifts to make the children happy. But what can we do when a bloodied man with open wounds strapped with an assault rifle and grenades shows up? One doctor agreed to collect and store all the weapons in his office. Also, the doctors had to find a place where to keep the dead bodies of soldiers. There was no fear, say the doctors. Nor was there any fatigue as adrenaline was on a high. ‘At 18:00 it’s already dark – we needed to put our lights out (‘light masking’ in order to make various locations less noticeable at night for safety reasons)’ says Liutkevych. ‘You walk along the stairs and you hear someone crying on someone’s soldier. Boys and girls. We tried to support one another, even make jokes. Sometimes, someone lets everything out through crying and then goes on to lift others’ spirits. It only became scary when the battles ceased and people started recalling how things were back then’.

At the start of the war, there were five prematurely born infants weighing around 900 grams. Normally, they would have to be placed in special incubators, where a microclimate would be created in order to accommodate their development. But what can be done when there is no heat in the radiators, no electricity? An incubator would not work under such conditions. Children’s anesthesiologists took the infants down into the basement where it was a bit warmer and tried to recreate the microclimate resemblant to that of an incubator. In the end, the children were evacuated.

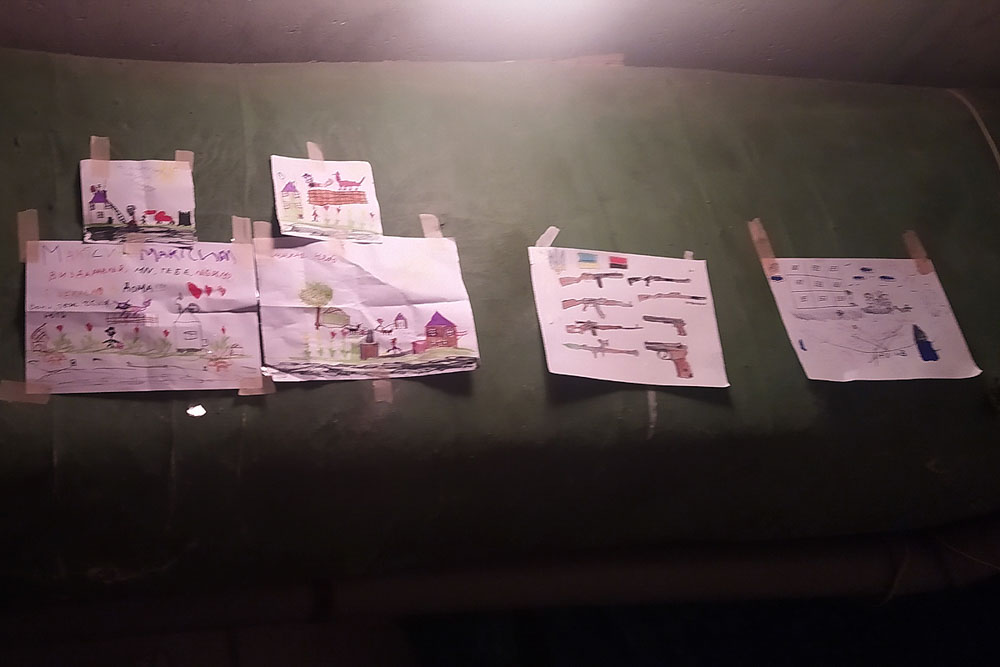

According to the doctors, the children in the basement adapted quickly to their new realities as long as father or mother was nearby and there was someone to play with. In such circumstances, no one wanted to separate the children from the rest. They have already seen everything: the blood and the corpses. Luckily, many of them were successfully evacuated after some time. However, until evacuation would take place, it was important to keep them busy. Henceforth, the doctors came up with a drawing competition for the children. They stacked up some paper sheets and handed them out. ‘Everyone asks us what gave us the energy to continue. This is what gave us the energy’. – said a traumatologist. ‘The belief that our children will grow up in a peaceful and victorious nation. There are explosions, there are many wounded and a lot blood, but the children are sitting here and drawing. Yes, our children are the children of war, but they will probably value Ukraine’s independence more than us’

Конкурс малюнків

Unfortunately, not all the children could be saved during this time. Two boys, aged 15, shot in a village near Chernihiv were not able to reach the hospital in time and died on the way. A 9 year old boy, who came under shell fire together with his parents, was surgically operated on for over eight hours, but his wounds were so severe that he passed away without leaving his state of coma two days later.

Recently, a borehole was established under the basement of the children’s hospital so that there would be an independent water source and people would no longer need to use ‘technical’ water from the pool. Moreover, there are far more generators now, enough to cover all the needs. All 327 windows as well as the roof which were damaged by cluster shells were all repaired. Yet, the war is not over, so the windows on the first floor are still covered by sandbags, and the light ‘masking’ routine is still in place. Just in case, the hospital keeps the minimum set of equipment in order to be able to set up an operating room.